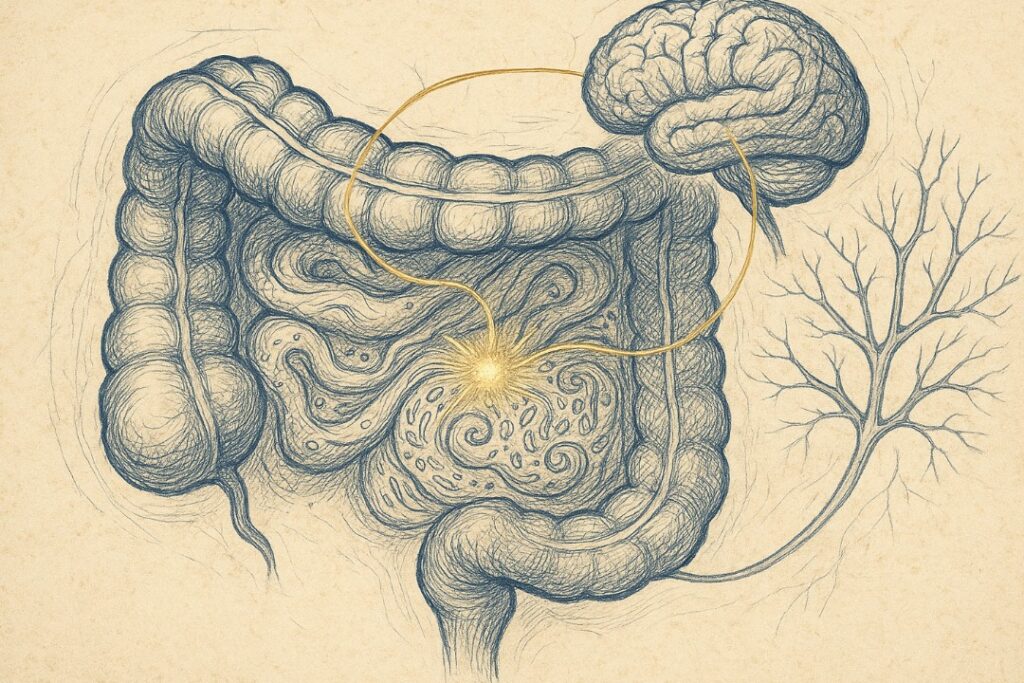

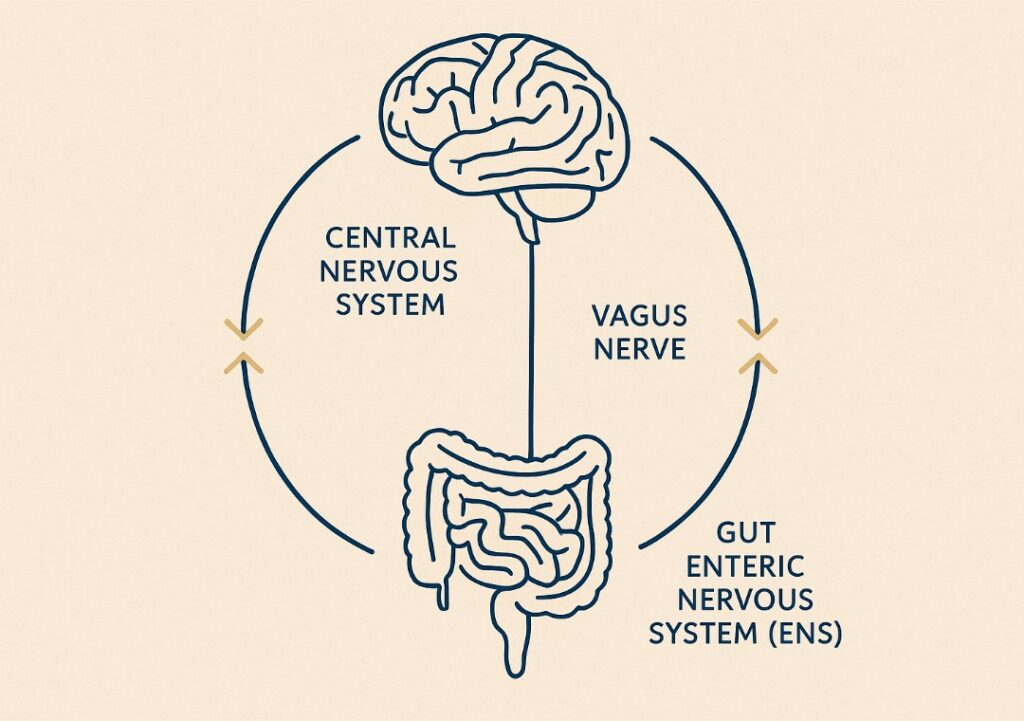

The Gut-Brain Axis (GBA) is your body’s most intricate communication superhighway, a bidirectional network linking the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to the

(CNS). It operates through an intricate web of pathways involving the autonomic nervous system, enteric nervous system, immune signalling, microbial metabolites, and endocrine hormones. The vagus nerve—the longest cranial nerve—acts as the primary communication highway, regulating involuntary processes and transmitting information about microbial composition, inflammation, and nutrient status.

This continuous dialogue ensures physiological processes like digestion, emotional regulation, immune response, and even skin health are tightly coordinated. This network allows not just for top-down signalling (e.g., stress impacting digestion) but also bottom-up communication, where the gut microbiota influences neurotransmitter production, neuroinflammation, and cognitive processes.

Uncover Advanced Protocols and Launch Access.

For those who champion evidence over hype.

Understanding the gut-brain axis is fundamental to appreciating how internal ecosystem imbalances can manifest as mood disorders, cognitive decline, immune dysfunction, and systemic inflammation—and why gut health is not just a digestive concern, but a central pillar of whole-body well-being.

Microbial Messengers: Serotonin, GABA, and the Neural Dialogue

One of the most fascinating aspects of the gut–brain connection is how your body uses neurotransmitters—chemical messengers—to facilitate dialogue between systems.

Serotonin

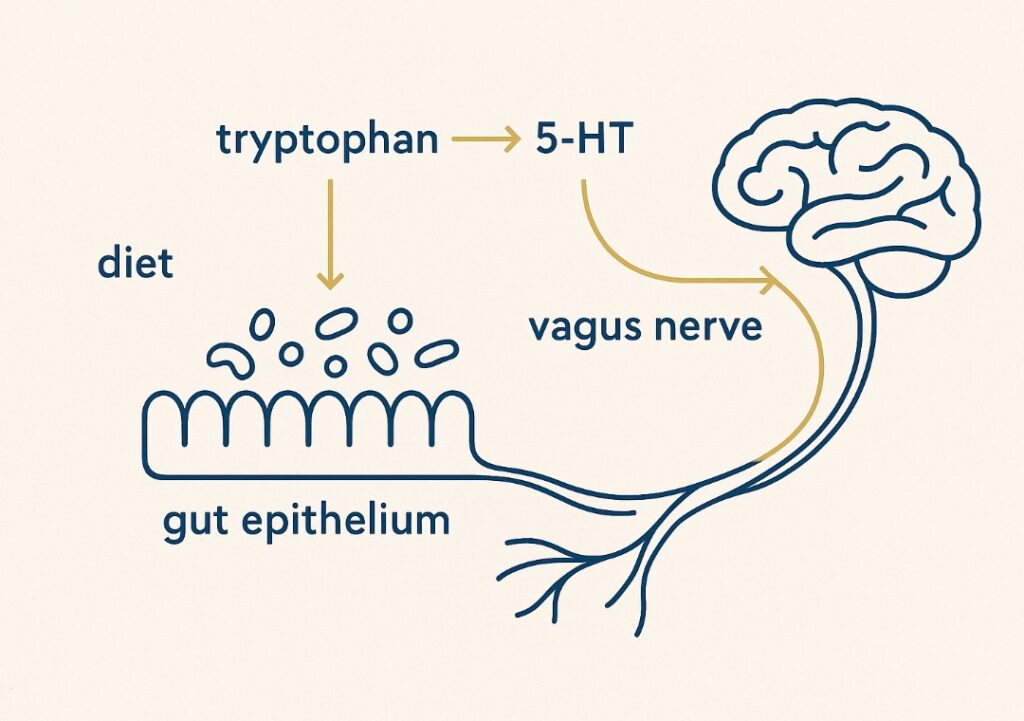

Serotonin (5-HT) is often dubbed the “feel-good” neurotransmitter due to its role in regulating mood, appetite, and sleep. Serotonin also acts as a mood stabiliser, playing a crucial part in emotional stability and mental well-being. While it is commonly associated with the brain, about 90% of the body’s serotonin is synthesised in the gut, specifically by enterochromaffin cells and certain gut microbes [Yano et al., 2015; Mawe & Hoffman, 2013].

The synthesis of serotonin depends on the essential amino acid tryptophan, which must be obtained from the diet. Emerging evidence suggests dietary tryptophan may modulate serotonin activity under certain conditions. Serotonin in the gut influences intestinal motility, secretion, and pain perception, [Fernstrom & Wurtman, 1971]. Emerging research suggests gut-derived serotonin may influence brain function indirectly through vagal pathways, though human evidence remains preliminary [Bonaz et al., 2018]. Altered serotonin signalling has been associated with conditions such as depression, anxiety, and IBS [Mawe & Hoffman, 2013; Bonaz et al., 2018].

GABA (Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid)

GABA is one of the main inhibitory neurotransmitters in the brain, responsible for calming neural activity and reducing anxiety [Wu, and Sun 2014]. GABA activity and levels are crucial for mental health, and imbalances can affect neurological and psychiatric conditions, including neurodegenerative disorders.

Several gut-resident bacteria, including Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species, are capable of producing GABA or modulating its activity through fermentation byproducts like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [Barrett et al., 2012; Diez-Gutiérrez et al., 2020]. You can read more about Short Chain Fatty acid in our dedicated journal (How SCFAs Build Your Foundation for Wellness). GABA acts on the enteric nervous system and communicates with the brain to help regulate stress responses [Krantis, 2000; Auteri et al., 2014].

Dopamine and Other Neuroactive Compounds

Dopamine, Acetylcholine, and Norepinephrine also have microbial‐production pathways or gut-mediated modulation pathways. Their effects on motivation, attention, and reward circuitry in human brains are increasingly understood to be co-shaped by gut flora and inflammation status [Chen et al.; 2021; Dicks 2022]. Imbalances in these neurotransmitters—whether due to dysbiosis, diet, or stress—can trigger mood disturbances, sleep issues, and metabolic dysfunction [Bamicha et al., 2024].

Gut Microbiota and Mental Health

Anxiety and the Microbiome

People with anxiety disorders often show a distinct gut microbial profile, characterised by reduced alpha diversity and lower levels of beneficial taxa such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Lachnospira [Jiang et al., 2018]. Concurrent analyses indicate an increased relative abundance of pro-inflammatory genera including Streptococcus and Fusobacterium [Simpson et al., 2021]. These microbial shifts can influence GABA and serotonin pathways, compromise intestinal-barrier integrity, and heighten systemic inflammation — all processes linked to anxiety and mood dysregulation [Kelly et al., 2016].

Depression and Dysbiosis

Clinical studies reveal that individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) often show reduced abundance of Dialister and Coprococcus — genera associated with SCFA production, particularly butyrate [Valles-Colomer et al., 2019]. You can learn more about Butyrate in our Journal (Butyrate Benefits: Its Role in Gut and Overall Health), These fatty acids support gut-barrier integrity and have demonstrated neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects in the brain [Silva et al., 2020; Dalile et al., 2019]. Emerging evidence suggests that modifying the gut microbiome through dietary changes, probiotics, and lifestyle interventions may help alleviate depressive symptoms, likely by restoring microbial balance and reducing neuroinflammation [Kazemi et al., 2019].

How Food Shapes Mood Through the Gut

- Tryptophan-Rich Foods: Tryptophan is an essential amino acid required for serotonin synthesis. Found in foods such as turkey, eggs, and oats, tryptophan must cross the blood–brain barrier to contribute to central serotonin production [Jenkins et al., 2016]. However, gut inflammation or microbial imbalance can divert tryptophan metabolism toward the kynurenine pathway — a biochemical detour linked to neurotoxicity and depressive symptoms [O’Farrell et al., 2017].

- Prebiotics and Probiotics: Prebiotic fibres from garlic, onions, leeks, bananas, and chicory root nourish beneficial gut bacteria, promoting short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production and reducing inflammation [Roberfroid et al., 2010]. Probiotic strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB-1 and Bifidobacterium breve have shown anxiolytic and mood-modulating effects in both animal and human studies [Akkasheh et al., 2016; Steenbergen et al., 2015].

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (EPA and DHA), abundant in fatty fish, help reduce neuroinflammation and support microbial diversity [Joffre et al., 2019; Watson et al., 2018]. They also enhance the formation of anti-inflammatory metabolites and pro-resolving mediators, contributing to mental clarity and emotional resilience [Ferreira et al., 2022].

Lifestyle Inputs that Modulate the Gut–Brain Axis

Chronic Stress and Cortisol

When the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is chronically activated, cortisol levels rise and can impair intestinal-barrier integrity, increasing gut permeability—often described as “leaky gut.” This weakening of the epithelial layer allows endotoxins such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to enter circulation and drive systemic and neuroinflammatory responses (Söderholm & Perdue, 2001; Maes et al., 2012].

Vagus Nerve Activation

Practices such as mindfulness meditation, diaphragmatic breathing, and yoga stimulate vagal tone. Higher vagal tone correlates with lower inflammatory cytokines, improved gut motility, and greater emotional regulation, measurable through heart-rate variability (HRV)—a non-invasive index of parasympathetic activity [Breit et al., 2018; Steinfurth et al., 2018].

Sleep and Circadian Rhythms

Gut microbes follow diurnal rhythms that mirror the host’s sleep–wake cycle. Sleep disruption alters microbial composition and reduces short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, which can dysregulate serotonin and GABA synthesis [Anderson et al., 2017; Grosicki et al., 2020]. Adequate, consistent sleep supports microbial diversity and sustains a balanced gut–brain dialogue [Smith et al., 2019].

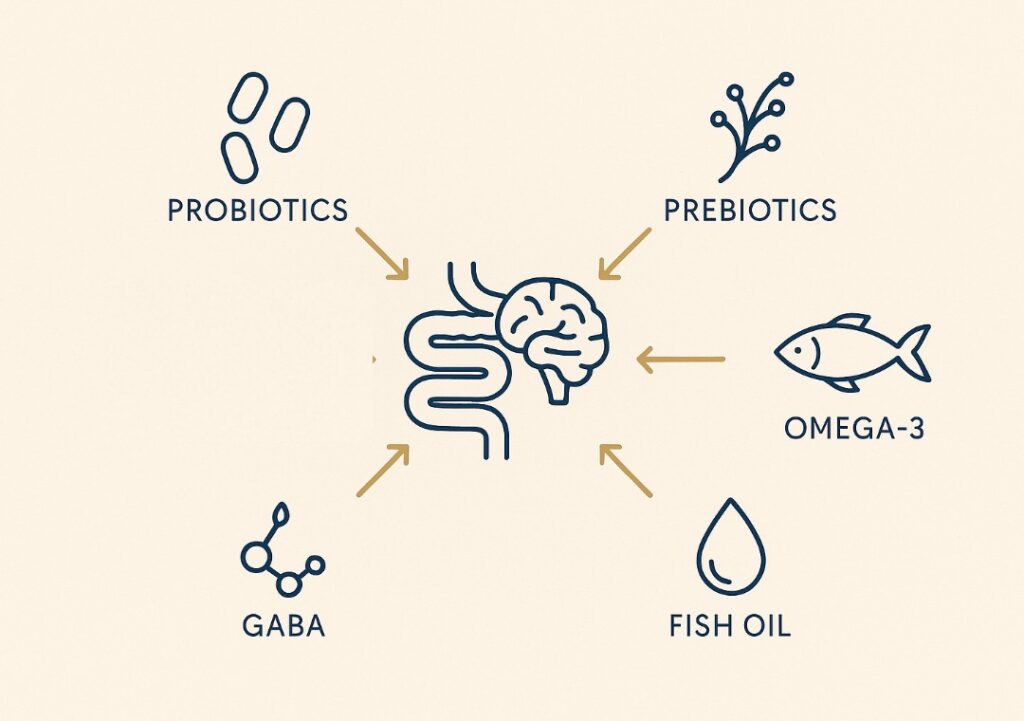

Supplements and Considerations

If dietary changes are insufficient, evidence-based supplementation may support gut–brain homeostasis:

- Probiotics: Specific strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1) and Bifidobacterium breve (MCC1274, M-16V) have been shown to modulate gut–brain communication, improve microbial diversity, and influence neurotransmitter pathways including GABA and serotonin signalling [Bravo et al., 2011, Kato-Kataoka A., et al.2015].

- Prebiotic fibres (inulin, FOS): Prebiotics such as inulin and fructooligosaccharides (FOS) fuel SCFA production and can positively affect stress-related behaviour and mood [Schmidt et al., 2015]

- Fish oil (EPA/DHA): Omega-3 fatty acids support cognitive health and modulate microbial anti-inflammatory signalling. Human trials show EPA + DHA reduce neuroinflammatory markers and enrich SCFA-producing bacteria [Watson et al., 2018].

- GABA supplements: The ability of oral GABA to cross the blood–brain barrier remains debated. Some small human studies report acute calming effects, likely via peripheral or vagal mechanisms, but overall evidence is limited; more research is needed. Always consult a clinician [Abdou et al., 2006; Nakamura et al., 2009].

The Gut as a Mental Health Ally: Nurturing Your Emotional Tuning Fork

Your gut is more than a digestive organ. By nourishing the microbiota with prebiotic fibres, fermented foods, quality fats, and a low-inflammatory lifestyle, you support the full intelligence of your biology.

From neurotransmitter balance to mood stability, the gut–brain axis plays a foundational role in both how you feel and how you function. Radiance and resilience are not just skin-deep—they are rooted in the trillions of microbial allies within.

Your gut is not just a digestive organ—it’s a neurochemical factory, immune regulator, and emotional tuning fork.